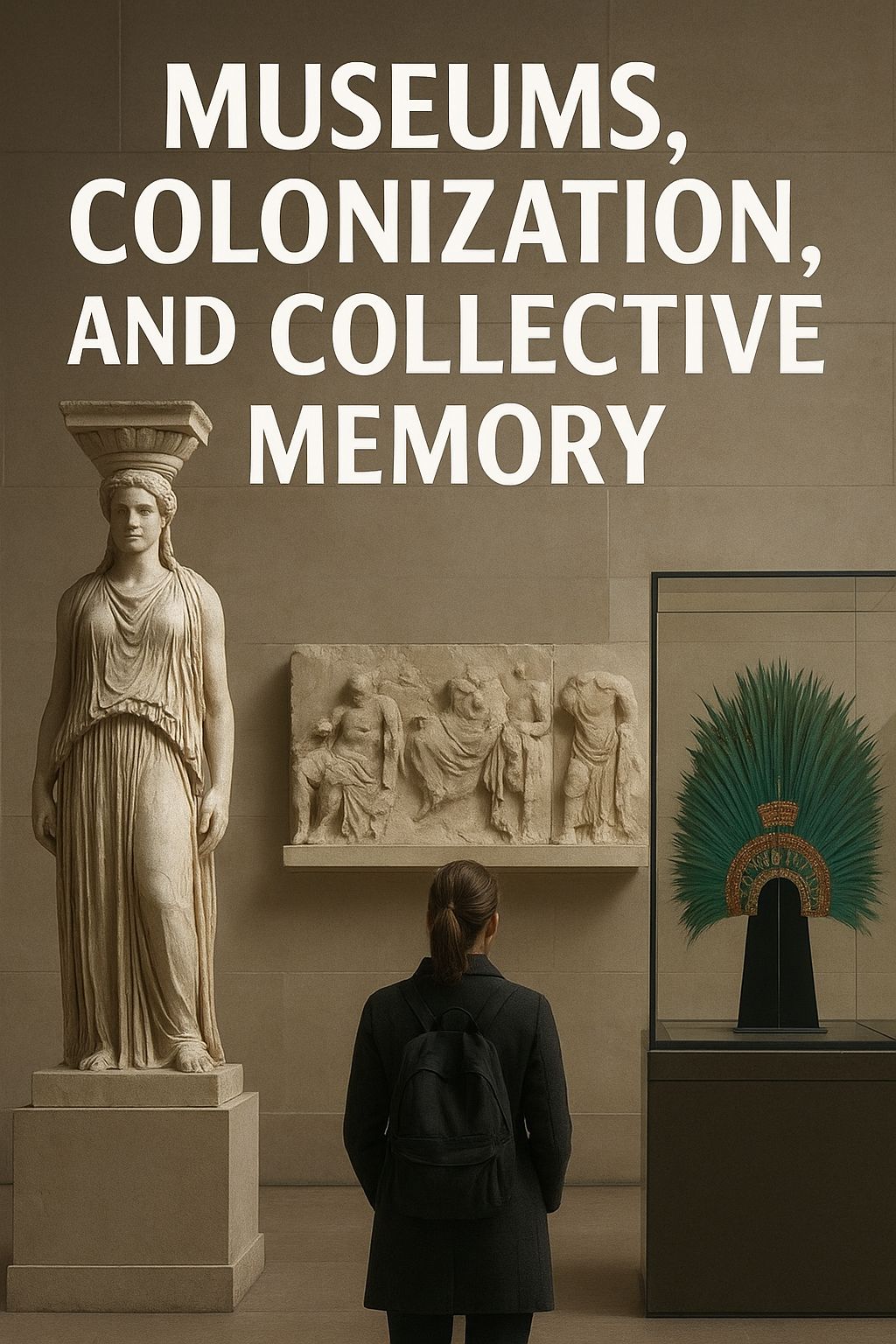

Museums often present themselves as temples of culture, guardians of memory, and spaces of learning. Yet behind their white walls and pristine vitrines lies a history of colonization, violence, and dispossession. Many of the objects we admire today were ripped from their original contexts in acts of plunder that accompanied conquest, genocide, and the imposition of colonial power. The world’s most prestigious museums are literally built on the remains of this looting.

A visible example can be found in the British Museum in London, where the so-called Elgin Marbles are displayed, along with one of the Caryatids from the Erechtheion. At the Acropolis Museum in Athens, five original figures stand together, with an empty space left where the missing one should be. That absence has become a living memory of theft. It is a reminder of how colonizing nations transformed sacred pieces into cultural trophies while continuing to charge tickets to admire them.

https://www.greecehighdefinition.com/blog/ancient-greece-essay

This same pattern is replicated across Latin America, only on a much larger scale. The entire continent was plundered—not only of gold and silver, but of symbols, codices, sculptures, masks, ritual garments, and objects of spiritual power. Moctezuma’s headdress, kept in Vienna, is perhaps the most infamous example. A masterpiece of precious feathers tied to Mexica power and worldview, transformed into an exotic display for European tourists. Austria boasts that Mexicans are granted free admission to see it, as if this were a gesture of generosity. It is not. It is not a favor. It is the bare minimum. Exhibiting an object stolen in the context of cultural genocide is not neutral: it is profit made from stolen memory.

https://www.nytimes.com/es/2020/10/18/espanol/opinion/amlo-penacho-moctezuma.html

And this is not limited to isolated cases. Pieces of Maya, Olmec, Zapotec, Moche, Inca, and Guaraní cultures are scattered today in the vitrines of Paris, Madrid, Berlin, and New York. Some were torn from temples; others were smuggled by European “explorers” disguised as archaeologists. The official narrative is always the same: that outside Latin America these objects were “safer,” that their “universal value” justifies keeping them abroad. But the uncomfortable truth is simple: they were stolen, and they continue to be exploited economically as part of the cultural prestige of the colonizers.

Every ticket sold in a European museum exhibiting Latin American heritage is a ticket paid to admire stolen goods. Every photo a tourist takes in front of a pre-Columbian mask abroad is part of a circuit of consumption that continues to benefit those who took what was not theirs. Meanwhile, in the countries of origin, these absences weigh heavily. They are gaps in national collections, gaps in identity, gaps in collective memory.

And that is the central point: collective memory is not built only with what is displayed, but also with what is missing. The voids in Latin American museums are silent witnesses to looting. Objects traveling the world under labels like “universal art” do not represent cultural neutrality: they represent the continuity of colonialism.

The debate over restitution is not an administrative matter or a diplomatic courtesy. It is a question of historical justice. The people of Latin America should not be expected to thank European museums for granting them free access to view what was stolen. They should not be asked to feel grateful for the “care” supposedly given to objects that survived precisely because they were uprooted from their lands. What was stolen is not to be thanked for: it is to be returned.

As long as Europe and the United States continue profiting from these objects, colonization will not belong to the past, but to the present—renewed daily in every museum hall. Until the plunder is reversed, Latin America’s collective memory will remain fragmented. Our history will remain trapped behind foreign glass, commodified, until what was stolen returns to where it belongs.